Book Review: “Guts” by Bob Lutz

Robert A. Lutz, the outspoken cigar-smoking fighter pilot who helped turn Chrysler around before it merged with Daimler-Benz in 1998, sat down and wrote a book on business before his brief retirement.

As Daimler-Benz and Chrysler were merging, Lutz, an vocal opponent of the merger and an instrumental part of Chrysler’s 1990s overhaul, was squeezed out, perhaps perceived as a threat to Daimler management, or a “disruptive change agent” as he describes himself.

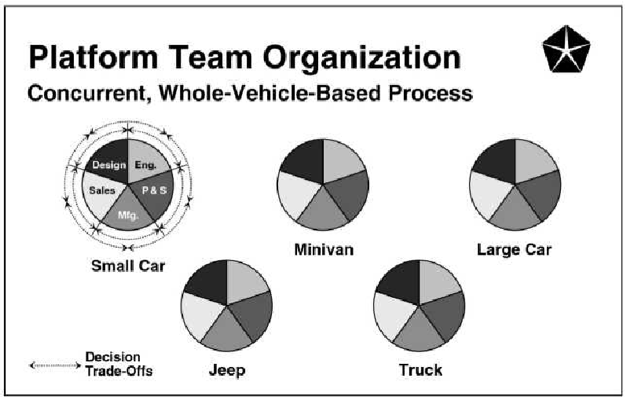

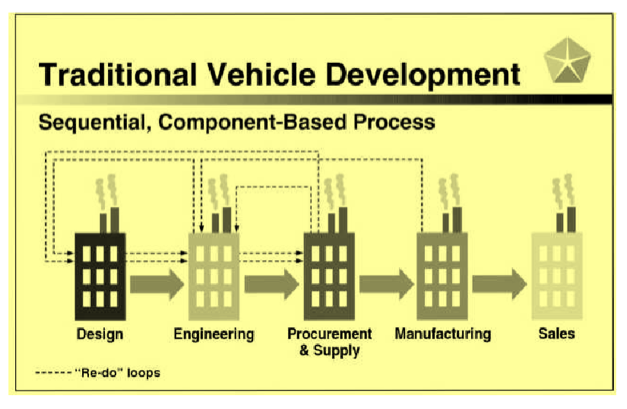

“Guts” goes into revealing detail explaining how Chrysler saved itself from bankruptcy by reorganizing its product development and detailing how the company designed, built, and engineered the Dodge Viper for only $80 million. The Viper program, it is revealed, was more than an exotic car project. It was a an experiment to test Chrysler’s new platform teams, groups of people with shared interest and fast communication, eliminating the delays, costs, and mediocrity caused by Chrysler’s bureaucratic structure.

Before instituting more cohesive supplier relationships, Chrysler took the same approach as Wal-Mart in procurement, aggressively demanding price concessions of five percent each year, or else. Suppliers were pitted against each other in a highly competitive auction process that guaranteed the cheapest part, quality be damned.

Chrysler learned to sit down and seek input from suppliers, fostering a more symbiotic relationship. As a result, savings were realized and quality slowly improved. And much like Wal-Mart, Chrysler learned to share cost savings with suppliers, creating a financial incentive for both parties.

He reveals Ford’s nitpicking, micromanaging, creativity-stifling culture of the 1970s and 1980s. A Polaroid Camera worth $25, used by a service rep to send pictures of parts (rather than the whole part) for warranty replacement approval was stolen. To receive a new camera and get on with business, the executive was asked by a panel:

Why does the company provide cameras in the first place?

Who pays for the film?

How do we know the reps don’t use the cameras on weekends to photograph their family?

Do we have controls?

Do we count films?

Why not?

How many packs are allocated per week to each service rep?

Who checks?

Who keeps the books on films?

This barrage of stupid questions was in spite of the fact that the camera saved Ford hundreds, perhaps thousands of dollars on freight costs. The executive who asked for a new camera said he would return in a few months with a report on how to monitor film usage. Ford rewarded sniveling, shit-eating, micromanaging behavior, and it resulted in forgettable and sometimes awful cars.

While reflecting on his youth, the Marine Corps, his time at UC Berkeley, and his time at BMW, Ford, GM, and Chrysler, Lutz shares his “Immutable Laws of Business,” listed below with brief summaries:

1. The customer isn’t always right.

Focus groups and surveys only reveal the present. They don’t create new paradigms or introduce new ideas. People in focus groups tend to be dishonest, presenting themselves as sensible when real purchases are often made on emotion and impulse, something that can’t be measured by Q&A sessions.

Lutz reveals how an excessive emphasis on marketing surveys caused the Shadow and Sundance to balloon in size, approaching Chrysler’s midsize offerings in dimensions but with much lower prices, adversely affecting profitability. The customer doesn’t see or understand the future — that’s what an auto manufacturer’s creativity and inventiveness are for.

Relying too heavily on the customer for input, says Lutz, is what transformed the Ford Thunderbird from a small, sporty two-door coupe into a characterless, two ton land barge.

Lutz discusses a part he encountered that was being produced for the upcoming 1995 Lincoln Continental. The Continental, apparently inspired by focus groups, attempted to please every customer by offering electronic settings to configure steering effort and suspension damping, supposedly to cater to both spirited and relaxed drivers. I’ve played with this system myself, and its completely pointless. It confused customers and made Lincoln look wishy washy and unsure of itself.

Instead of making a clear decision on how the car should drive, Lincoln farted out a watered down example of what was otherwise an excellent car. In later model years, these idiotic settings were removed.

Across town, GM’s Cadillac Seville STS was much more expensive, used cheaper interior materials, and was generally less reliable, but the Seville was sure of its character and mission and handily outsold the everything-to-everyone Lincoln. [I’ve owned three Cadillac Sevilles and zero Continentals… partly because of this.]

Girls hate it when guys let them make all the decisions. No one loves a wuss. No one likes unfocused products.

2. The primary purpose of business is not to make money.

In his own words:

“What I mean to suggest with this Law, however, is that companies that do make a lot of money almost never have as their goal “making a lot of money.” They tend to be run by enthusiasts who, in the normal course of gratifying their own tastes and curiosities, come up with products or services so startling, so compelling, and so exciting that customers practically rip their trouser pockets reaching for their wallets.”

For example, the purpose of Wal-Mart, when Sam Walton was running it, wasn’t entirely to make money. His motives were competition, action, and victory — profitability tagged along for the ride.

3. When everybody else is doing it, don’t!

Companies have a compulsion to follow fads. Executives read the pages of the Wall Street Journal and Forbes asking themselves, “Why aren’t we doing this?” The consultant selling the shiny new idea is hired at a hefty hourly rate to speak to the company and advise managers. Before soon, the same magazines and newspapers that had praised the latest, greatest fad are suddenly publishing critiques, asking how so many managers could fall for such a short-sighted plan.

Lutz also stresses the need for creativity and innovation. He depicts the soft drink market before Coca Cola on a pie chart. You have one third tea, one third coffee, and one third juice. As far as anyone knew, that was it, and new competitors simply made tea, coffee, or juice. Then along came Coca Cola, busting the pie open and adding a new soft drink category instead of following everyone else.

The same could be said of the large crossover segment, pioneered by Chrysler with the poorly executed but clever Pacifica. Now, American roads are filled with Buick Enclaves, GMC Acadias, and Honda Pilots.

4. Too much quality can ruin you.

Of course, too much of anything can ruin you, and the worship of quality can create tunnel vision. Rolls Royce “cleaned” the GM Hydramatic transmissions installed in its cars, resulting in incorrect fluid pressures and poor shift quality. Chrysler, for half a century, installed its lug nuts with reverse threads thinking that normal threads might spin off and cause the loss of a wheel. After decades of realizing this wasn’t the case, Chrysler switched to normal (righty-tighty/lefty-loosey) threads.

And, explains Lutz, there’s more to satisfaction than quality, which, based on surveys, is merely the absence of defects rather than the presence of greatness. “Given two extremes-‘zero defects with no delight’ and ‘delight with a few squeaks in it’-the public will always buy the latter.”

Of course, I might disagree with him and note that the Toyota Camry, a lifeless lump designed for sad sacks, is a top seller. On the other hand, the zippy, high-tech Ford Fusion is gaining momentum. Maybe there’s hope for American drivers.

5. Financial controls are bad!

“Tight controls do harm in two ways. First, they can jeopardize an organization’s ability to exploit big opportunities. While I was at Ford of Europe, for example, one of our products was getting murdered in the market because it lacked a then-high-tech cassette tape deck. It was a matter of our spending $40,000 (the cost of engineering and tooling for the tape deck) in order to protect an $8 million business. Finance balked!”

He explains that strict controls without a regard for growth, for creativity, and for common sense will doom an organization to mediocrity. He uses the $25 Polaroid camera at Ford as an example. There is a strong tendency for overly strict financial controls to only maintain the status quo.

6. Disruptive people are an asset.

Bob Lutz, of course, classifies himself as a disruptive person. He goes on to distinguish the difference between people who vocalize their concerns and push an organization to improvement… and people who are nuts.

“Sometimes the temptation to fire all disruptives can be keen. Resist it. Removing irritants feels good, but only in the same way that changing doctors feels good when your old one has been needling you to lose weight. Switch doctors however much you like, you’re still fat.”

7. Teamwork isn’t always good.

Citing Hollywood’s recycling of themes as an example:

”Me-too movies, like most other mediocre products that stumble gracelessly to market, are the fruit (mealy fruit, I might add) of too much teamwork. Teams prefer the safe, the familiar, the middle of the road, the well-researched. They fear originality.”

“In truth, most groups, left to their own devices, devote far more time and effort to the practice of teamsmanship (promoting group harmony, smoothing and protecting everybody’s ego) than they do to working.”

“The ability to compromise is, of course, a wonderful thing. And the promotion of team members’ self-esteem is, of course, a noble goal. But neither is an end in itself. We’re not running major corporations in order to perform social experiments. We are attempting to get work done. Remember work? It’s what’s required of us if we are to create the breakthrough products our shareholders expect and the public demands. And if that means, every so often, that we have to let some of the steam out of someone’s self-esteem, I say fine; so be it.”

————————————–

Part 3 of the book rambles on a bit, with Lutz sharing his views on education, politics, military service, and declining American culture. It starts to sound a bit like a BIll O’Reilly book, with personal experiences muddied by inconsistencies.

For example, he rails against the federal government for being too large, too controlling, and against free enterprise. With this, I agree, but he then suggests that the US should have compulsory military service, like Switzerland, to instill character into the citizenry, to counteract the “Fear Factor” generation. [If you recall, Fear Factor was a reality show on NBC back in the late 90s. People ate bugs and acted like desperate morons for a little bit of money.]

That sounds like a massive federally-funded social experiment.

You cannot criticize the government for stifling the rights of a free society while demanding that the same government send the unwilling to war. The Marine Corps, he says, did wonders to turn him around, to drag him out of his wandering youth and give him a sense of purpose.

Lutz, a product of wealth and privilege, assumes that the rest of us need military service to become decent people. What he neglects to acknowledge is that some of us already have our heads screwed on straight and don’t require millions of federal tax dollars in combat pilot training as an expensive form of therapy.

I congratulate him for his accomplishments and his strong moral character, but I take issue with being forced at gunpoint to give my productivity to a government that he acknowledges has little respect for my freedom.

[I hate getting into politics on this blog.]

He also talks about how we should complain more about bad service at restaurants.

————————————–

In most of “Guts”, Lutz praises Chrysler’s merger with Daimler Benz as a positive step in a new direction. Hindsight is 20/20, and its unfair to criticize him for being wrong about a merger that most people perceived as productive. And in fairness, he mentions in his new book “Car Guys vs Bean Counters” that he misjudged the success of the merger.

The epilogue was written just after Jurgen Shrempp was ousted from Daimler Benz but before the involvement of Cerberus, the US Treasury, and FIAT. He gives his version of how things went wrong, suggesting that a major part of the issue was that the Germans broke up Chrysler’s executive dream team. Lutz, Castaing, Pawley, and CEO Bob Eaton had retired or been replaced.

Bob Eaton, one of the original architects of the merger, has more or less gone into hiding. I would perhaps do the same if I were him.

“Daimler management failed to understand the change that had occurred. They assumed that even though the roster of senior talent had been shuffled, ‘Chrysler would still be Chrysler’ and that the company’s mastery of its business would continue as before.”

Perhaps, then, its possible to say that Chrysler’s culture was too dependent on a few charismatic leaders rather than a companywide, deeply instilled, fundamental cultural change. Its the dilemma facing Apple as CEO Steve Jobs undergoes treatment for pancreatic cancer. Can the ship keep moving without its talented captain?

Likewise, GM’s recent product turnaround happened under the guidance of Lutz who was fired after the US Treasury took ownership in 2009. Was Lutz able to instill long-term changes at GM, or will product development suffer as it did after he and others left Chrysler?

The Germans at Daimler, he says, tried to mask falling sales and rising costs by pushing leases, which adversely affected resale value and made subsequent leases too expensive:

“The lesson here is that a car company pulls the lease trigger too aggressively at its peril: You can look good today and pay dearly in two years, or you can admit up front that you have problems ‘making the numbers’ and cut production now. It’s really a simple matter of pay now or pay later.”

“Needing to buy time, they gambled that an incredibly buoyant used-car market two years down the road would soak up all those off-lease vehicles. It didn’t.”

He then explains that the Germans should have, at the risk of hurt feelings, pushed harder to integrate Chrysler into its corporate culture:

“In order to realize the promised savings and offset the inevitable operational slowdown during the assimilation process, it is imperative for the dominant partner in the merger to move rapidly to impose its structure, its metrics, and its executive appraisal systems-in short, its entire operating philosophy, plus that qualitative thing called culture. Somebody has to be the boss!”

His last comment on the merger is this:

“If it’s a merger, the weeding out must be done gradually: You need enough people to be able to conduct business during alterations. If it’s an acquisition, though, your only option is to move fast and let all heads role at once.”

He neglects to mention that Chrysler’s merger with Daimler-Benz was a fraud. It was, in reality, an acquisition, and the lies that sold the takeover to shareholders resulted in half-assed, slow-moving measures by German management concerned about looking predatory.

Everyone suffered as a result.

————————————

Finally, at the end of his epilogue, Lutz adds one additional rule:

8. When you inherit a really big rat’s nest, don’t try to lure them out with food. Use a flamethrower.

“No matter how good the acquired (or merged) company, digesting a corporate body almost as big as one’s own presents peril, not just opportunity.”

Citing IBM’s Lou Gerstner as an example, Lutz says a newly acquired firm has to flush out dead weight in order to adopt new practices and philosophies. As an example of a poorly executed acqusition, he mentions Rover. Billions were poured into the company while BMW’s management took a hands-off approach. It got to a point where the Rover division, operating autonomously within BMW, dragged down the entire company and was sold for one dollar to Ford (Mini was retained).

————————————

Lutz concludes with the following:

“I don’t know how DaimlerChrysler’s story will unfold. There were, undeniably, some initial mistakes made in the mega-merger-as how could there not be in any undertaking so enormous? I do know, though, that when the last chapter is written, the controlling factor in the company’s success or failure won’t be that it took a few missteps. We all do that. It will be how well the executive team members toughed it out, how well they fought their way back to a true course, how well (if I may be permitted one last word) they showed guts.”

Well, we all know how that turned out. They got gutless and farted out half-hearted, half-assed, half-baked lumps like the ungainly 2007 Sebring, the pointless Jeep Compass, and the crude and disposable Dodge Caliber. The Dodge Viper, a modern American icon and the heart of Chrysler’s 90s revival, was discontinued (for a few years, but new owner Fiat says a new Viper is under development).

Instead of taking risks with bold designs and innovative products as it did before, the company rolled out compromised turds that looked like they were heavily influenced by focus groups, and the participants were apparently a bunch of aging lesbians with cataracts.

Once a beacon of hope for American manufacturing, Chrysler became a go-to example of everything wrong with Detroit. And once again, the company stood in line applying for federal assistance, this time alongside the once formidable giant General Motors.

I’m cautiously optimistic about Fiat’s involvement, however, and products like the new Dodge Durango, Jeep Grand Cherokee, Dodge Ram, Pentastar V6, and dramatically revised Chrysler 300 serve as evidence that the spirit of innovation is still alive at Chrysler.