The auto industry is more than a century old, so the passing of well-known leaders, engineers, and designers is nothing new. We remember names like John Z. Delorean, Ransom Eli Olds, Harley Earl, Henry Ford, Karl Benz, Walter P. Chrysler, and Alfred P. Sloan. They each moved personal mobility one step forward, changing the way we interact with the world, the way we express ourselves, and the way we live, but most of them died several decades ago.

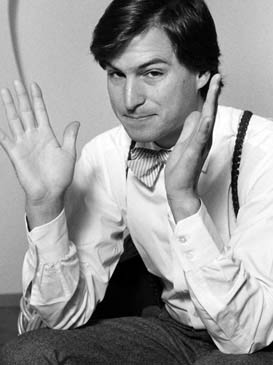

By contrast, the bigger names and faces in Silicon Valley are young, still working, and very much alive. Generations of people have passed through the corridors of General Motors but Apple, founded in 1976, is a relatively young company. Therefore, Steve Jobs’ death at the age of 56 is quite jarring. He continued to serve as Apple’s CEO until stepping down weeks earlier due to health concerns. Then, on October 5, 2011, he passed away after a battle with pancreatic cancer.

Compared to automobiles, personal computers are relatively new, arriving in the 1970s and maturing at the end of the 1990s. What was once a luxury for upper class families became as ubiquitous as flush toilets, occupying most American homes by the end of the last century. Then, on the coattails of the PC came a wave of smartphones, PDAs, and personal multimedia devices that revolutionized communication and further connected the human race. It sounds quite similar to the story of the automobile.

Industrialists like Henry Ford and Michael Dell focused on volume, cost, and operational efficiency while design visionaries like Harley Earl and Steve Jobs emphasized human expression, emotion, and interaction.

Before assembly-line manufacturing, the automobile was an expensive toy for the wealthy, a novelty for the privileged and accomplished. Streamlined manufacturing introduced by Henry Ford and Ransom Olds significantly reduced assembly times, increased production output, and contributed to per-unit cost savings that lowered prices for consumers. Suddenly, almost overnight, America was on wheels.

Likewise, MITS (Altair), Tandy, Compaq, IBM, and Commodore played significant roles in reducing the cost of PC technology, transforming home computers from pricey, finicky toys for hobbyists to low-cost mass-produced boxes with wide functionality. The day finally arrived where if you wanted an affordable computer, Radio Shack and Sears-Roebuck carried a wide selection, all in beige. No soldering necessary.

Using a computer back then, as I remember it as a child of the 1980s, was like driving a Model T, an unintuitive process involving specific commands and strict syntaxes, like the mess of knobs and levers on a Model T Ford. The functionality was there, but accessing it was a chore.

The arrival of electric starters, seat belts, power steering, heating, and air conditioning brought civility and comfort to American motoring the way Steve Jobs and Apple brought ease and simplicity to computing. What was once the domain of a handful of enthusiasts became tangible and accessible to the masses.

It’s important to note that Steve Jobs didn’t create the personal computer, the smartphone, or the MP3 player (the Diamond Rio predates the iPod). Calling Jobs an inventor would be fairly inaccurate.

He was instead a planner, a conceiver, and a dreamer. To offer a cartographical analogy, he drew up a roadmap depicting the future while delegating others to build the roads. That’s the heart of leadership, and it makes up the bulk of his legacy.

Others will remember his lack of philanthropy, his draconian and sometimes ethically questionable management style, and the two years his daughter Lisa and her mother Chris-Ann spent living on welfare while he denied paternity.

For better or worse, he will be remembered.

Very interesting and apt analogy.